The following notes are partly based on a lecture entitled ‘Egyptology vs Conspiracy Theory – why Egyptologists really matter in the 2020s’ which I was invited to give in Pisa in September 2025.

In 2024 I gave a lecture on ‘Pyramid Mythbusting’. As I explained here, I was moved to do this by the profusion of ‘alternative ideas’ about the age and function of the pyramids of Giza in particular. I wanted to show that the conventional view, i.e. that the Giza pyramids were built in the Egyptian Fourth Dynasty as tombs for the pharaohs of the time, is the interpretation that best fits with the evidence we have, and that the alternative ideas are generally not backed up by any evidence at all. I admit I was partly just exasperated by all the online comments querying the conventional view, but I also felt that this fed into the wider issue that significant numbers of people are sceptical about experts and prepared to believe any old bunk they see, particularly online – some of it deliberate misinformation circulated by individuals or corporations with dubious motivations.

Not long afterwards I was invited to give a lecture in Pisa as part of the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the first Egyptology class to be given in a university – in Pisa by Ippolito Rosellini in 1825. The organiser, Professor Gianluca Miniaci, had asked for something touching on one or more of the following themes:

“important milestones in the history of Egyptology, including current discoveries and research, deconstruction of “false myths” (assumptions), and new methodological approaches to Egyptology.”

I decided this was the moment to tackle the problem of ‘alternative truth’ in Egyptology and more widely.

I started by using the pyramids to exemplify the problem of alternative ideas circulating and potentially gaining more traction than the conventional wisdom. I summarised my ‘Mythbusting’ talk, covering when and how they were built, what their purpose was, emphasising the evidence used by Egyptologists to construct the current consensus view. I also took on the curiously prevalent idea that Egyptologists are hiding something…. For more on this please see my piece ‘Pyramid Mythbusting: further thoughts…’ where you’ll also find a link to the original lecture itself.

(In)Accuracy in News Reporting

In Pisa, I went on to talk about what you might call ‘bad Egyptology’*, starting with the recent discovery of the tomb of Thutmose II, the announcement of which contained several alarming inaccuracies. I wrote about this at the time, here (scroll down to ‘False Claims’), and gave lecture about it in December last year (2025).

And then, after I had already sent the lecture title off to my colleagues in Pisa (‘ I came across what seemed to me to be an even more worrying example of ‘bad Egyptology’.1

(In)Accuracy in traditional Publishing

In June 2025 I did an interview for an American TV series. As is fairly normal with these things the production company sent me a list of questions in advance. This is very helpful: it gives me a chance to do a bit of prep on any topics I don’t feel I know well enough; and perhaps more importantly it gives me a chance to query anything that doesn’t seem right or that could mislead the viewers. I’ve done quite a lot of TV over the years (see here) and my experience has almost always been very positive. The people who make these programs – TV professionals – usually do a great job with their research by reading around their subjects thoroughly and by contacting credible specialists like me for help. Occasionally something gets misunderstood or a little bit of dubious research or a dodgy claim informs a part of the script, but that’s partly why people like me get involved – whether on or off camera our expertise helps to make sure that the finished product is informed by good Egyptology.

in this latest instance, one of the questions I was sent in advance, about tomb KV 55 in the Valley of Kings, gave me a reason to go back to the producer with a query.

Q: “Please describe the curious inscription carved into the tomb’s wall: ‘The evil one should not live again.’ What do you make of this inscription?”

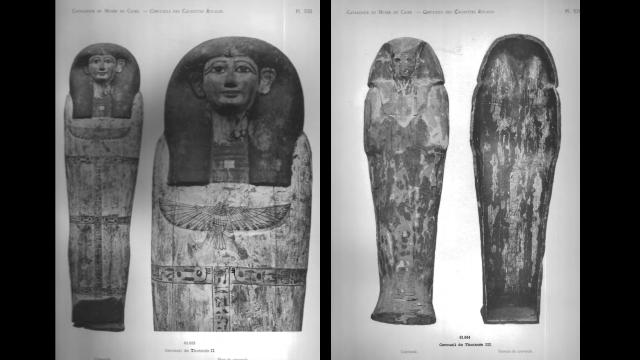

Me and the coffin from KV 55 in the Egyptian Museum, with the case removed for the making of a documentary in 2017.

I know KV 55 pretty well. It’s at the centre of one of the great debates in Egyptology (the identity of the mummy found inside), I wrote about it in my Lost Tombs book, I’ve often lectured about it, and although it’s not open to the public I’ve visited it several times. For all the discussion it has generated there’s actually not much to KV 55 – it’s a fairly small tomb as these things go, it didn’t contain that much material, very intriguing though it all may be. I had never heard of this inscription before, and I had always understood the tomb to be undecorated… Furthermore, this inscription, which is given in English translation only, sounded incredible – I could well imagine why a TV company would want to ask an Egyptologist about it. In fact, however, it sounded too good to be true – I couldn’t imagine which Egyptian words and phrases would lead to a translation like this. So, for all these reasons, I was suspicious to say the least but rather than go bowling in and telling the company that this was all nonsense, I asked them if they could provide me with the source of the information. The producer came back straight away with reference to a book I had never come across before (this one). It had been published fairly recently (2018) by someone I didn’t know personally but who I know by reputation and who, indeed, is described in the advertisement of the book on Amazon.co.uk as a ‘Famed Egyptologist and documentarian’.

The suspicious inscription provides the title of the book and appears prominently in its description on Amazon. I bought an electronic copy straight away so that I could check it for references but I couldn’t find any. Some books, even on academic subjects, don’t contain any such references, particularly when they are written for non-specialist audiences so although this was frustrating, it didn’t exactly seem scandalous.

I then set about checking the original excavation report (Davis, The Tomb of Queen Tiyi) a copy of which I have in my library, then several other articles reanalysing the excavation – because the original report from 1910 was so deficient. I could find no reference to any such inscription, and indeed no reference to any descriptions having been found on any of the walls anywhere in the tomb – as I had expected. I also checked with a colleague who is one of the world’s leading experts on this tomb, the material and the debate. He was unaware of this inscription and indeed made the very good point that of anything like it did exist it would be debated to death by Egyptologists!

I’ve since tried to contact the author of the book via his website and social media but have received no reply.

I don’t want to think that the author just made this up but at the moment I haven’t got a better explanation. Have I missed something? Is it possible that this book is in fact not meant to be a book about Egyptology as such but something slightly different like a kind of semi fictional Story? If so it’s fooled me – it seems like it’s intended to be a book about ancient Egypt. And of course, the author is apparently an Egyptologist after all.

If, however, the inscription has been made up, and yet the book is is intended to be read as a book about ancient Egypt by a qualified expert, then it must be one of the worst examples of bad Egyptology I have ever come across.

—–

All the above – alternative theories, the suspicion that Egyptologists are hiding something, misinformation, bad Egyptology – matters because of what’s going on in the wider world at the moment. We live in an age when politicians are, more so than ever in recent memory, prepared to make stuff up to influence their electorates, and to decry anything that doesn’t suit them as ‘fake news’. What’s not true can seem to be true, and what is really true can seem to be false. The switch from old to new media has made this possible and amplified its effects. In the pre-digital age, there were far fewer channels of communication – newspapers, magazine, books, TV, radio – and the landscape was simpler. It’s not that everything was produced by professionals, or that none of these channels was subject to any bias, but the content was more likely to be produced by professionals, and subject to editorial standards and controls. There is now simply so much content, and so many channels – think about the number of accounts across the major social media platforms – that’s its impossible to keep on top of everything, and correspondingly harder to know to what the extent the information is being conveyed accurately and without bias. We know that ‘information’ of dubious accuracy, is being used in dubious ways to influence the way people think and behave.

It seems to me that the new media landscape, the manipulations of truth, is encouraging a distaste for experts, and giving false legitimacy to alternative ideas, or even ‘alternative truth’. And I wonder if it’s this new world, that has allowed a supposed expert in Egyptology to sell a write a book, the hook for which is just made up.

You could argue that there are more important things in the world than Egyptology, and you would perhaps be right. But, Egyptology is an empirical discipline. Its goal is to increase knowledge and understanding of humankind in the ancient past, in Egypt, and it does this by gathering evidence of various kinds, mainly, where most of us who call ourselves Egyptologists are concerned archaeological or textual, but potentially drawings on innumerable other scientific disciplines. The evidence is gathered, documented and published according to certain conventions and standards so that it can be scrutinised by anyone with an interest, and then interpreted. We don’t always agree with each other in our interpretations, but as long as the original sources of information are signposted that’s not a problem – anyone who might disagree can check back, and come to their own conclusions. Generally speaking what gets published – the documentation of the evidence and those interpretations – is subjected beforehand to certain editorial processes to ensure that standards are met and interpretations are justified by the evidence.

This applies, of course, to academic papers, but also to material intended for wider audiences including TV documentaries. In other words what gets out there is generally good, or at least it would be if it weren’t for all the unqualified people and lack of editorial control online…

(I’m aware of course that there’s an irony in my posting this to my blog – online, and without any editorial controls. But I can at least demonstrate my credentials and in fact this is making me think that I need to make them clearer – perhaps I’ll post a CV!)

—–

At around the same time as I came across the rogue book on KV 55, the story broke in the UK media that a celebrated memoir, The Salt Path by Raynor Winn, which was about the healing power of a long-distance walk along the south coast of England, was exposed as having been not a true story as it claimed, but made up.

The book had been wildly successful, made the author a lot of money, and most worryingly may even have inspired some people to ignore conventional medical wisdom in favour of trying to cure serious illnesses with nothing more than a bracing walk.

My talk in Pisa included a number of quotes from the reporting, in particular in articles by Chloe Hadjimatheou, the investigative journalist who broke the story in The Observer, as they seemed to resonate with some of the concerns I had about bad Egyptology, and why we should be worried about it:

“Our reporting has found sins of omission and commission in The Salt Path. Leaving stuff out is run-of-the-mill for a memoir, but the sin of commission – inventing important passages of the book – is not.”

““We are deep enough into the post-truth world to know that if the idea of truth is mis-sold the idea of truth takes a knock, one that can make a small contribution to a huge problem.”2

The Rise of AI …and ‘AI Slop’

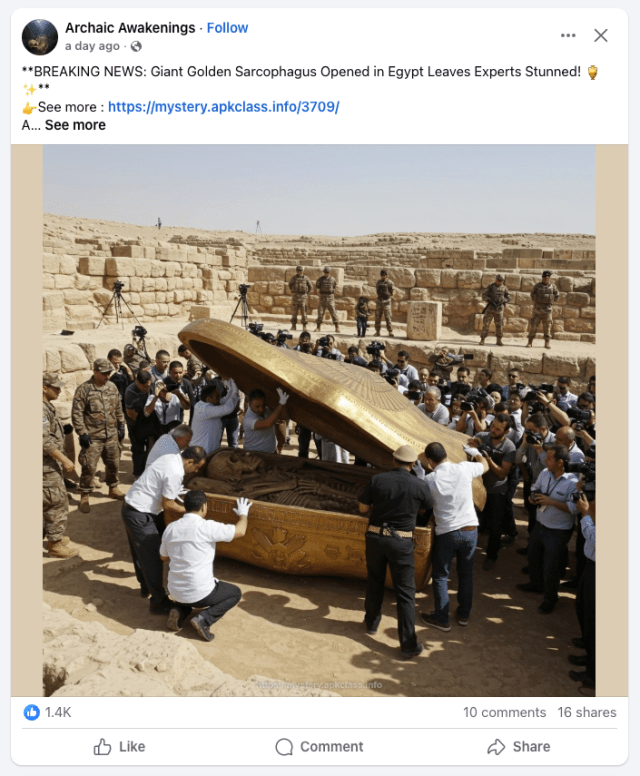

Perhaps worst of all, it seems that Egyptology-related content on social media platforms – which as we all know have enormous reach – are gradually being over taken by fictional stories of discovery accompanied by artificial images generated by AI, but which purport to be genuine. I have already had to set the record straight once or two in response to questions from Egyptophiles about such ‘discoveries; but there is now way any of us will be able to keep up with the slew of ‘slop’ now appearing on Facebook in particular. Handily for me, I began to see this trend reported , with appropriate concern, in the traditional media as I was preparing my talk, and again I included a few quotes in my presentation.

From The Guardian:

“There are two parallel image channels that dominate our daily visual consumption. In one, there are real pictures and footage of the world as it is: politics, sport, news and entertainment. In the other is AI slop, low-quality content with minimal human input.”

“Most of the time, AI slop is just content-farming chaos. Exaggerated or sensationalised online material boosts engagement, giving creators the chance to make money based on shares, comments and so on. Journalist Max Read found that Facebook AI slop – the sloppiest of them all – is, “as far as Facebook is concerned”, not “junk”, but “precisely what the company wants: highly engaging content”.”3

Egyptology-related AI slop on Facebook #1. September 2025

Egyptology-related AI slop on Facebook #2. September 2025

From The Economist:

“Since the launch of Chatgpt in late 2022, people have embraced a new way to seek information online. Openai, the chatbot’s maker, says that around 800m people use it. Chatgpt is the most popular download on the iPhone app store. Apple said that conventional searches in its Safari web browser had fallen for the first time in April, as people put their questions to ai instead.”4

Chat GPT

I have also noticed that the sort of people who are interested in ancient Egypt who might read one of my books, watch a TV documentary, listen to a lecture or a podcast and so, are now turning to ChatGPT and similar tools for answers to their questions:

From an email to CN, June 2025:

“Hello Chris,

Given statues of Akhenaton showing feminine features, does this indicate the ancient Egyptians had a modern day distinction between an individual’s biological sex and their gender identity?”

“I posed the same question to ChatGPT…; ChatGPT’s conclusion was “Yes — the evidence strongly implies that the ancient Egyptians understood gender as socially and symbolically constructed, separate from merely physical/biological sex”,

But what was this evidence…? Where is the AI’s information coming from? ChatGPT etc. provides no information about their sources.

It’s essential for us – Egyptologists and all academics – to be able to demonstrate where our information comes from, what the justification is for what we are saying – so that others can retrace our steps and understand the basis of what we know, challenge assertions we have made, or provide new interpretations.

The Distrust of Experts…

Connected to all this, just when trained specialists in Egyptology and any other serious scientific discipline are really needed to provide a counter to all the poor reporting, bad science, AI slop and so on, there is a parallel distrust of experts, exemplified by the British politician Michael Gove’s statement from around the time of the referendum on the UK leaving the EU (which he supported) that “I think that people of this country have had enough of experts.”

I quoted the response of Richard Portes, Professor of Economics at the London Business (‘Who needs experts?’) to this phenomenon:

“In certain segments of the population, there is undoubtedly a considerable distrust of experts.”

“…distrust has been encouraged by those who have vested interests in discrediting experts because they want to advance a particular agenda – be that in the field of economics, climate change, health or whatever – which may conflict with what expert opinion would be.”

However…

“…experts genuinely do try to test their own findings; they are prepared to be self-critical; in short, they try to get things right. For academics, that is part of the ethics of our profession.”

“experts are useful; they can deliver insights and help make the world a better place.”5

What can we do?

Of course, history is really important. We need to know what has happened in the past, where things led, and where they might go if we make the same mistakes. Historians, archaeologists, Egyptologists… are the experts with the knowledge. It’s vital that we are heard over the din of fake news, AI slop and so on.

What can we do? Is there anything we can do? Well, first of all, we must carry on i.e. researching, acquiring knowledge, proposing new interpretations, but most importantly, disseminating…

I was reminded at this point of a favourite quote of mine:

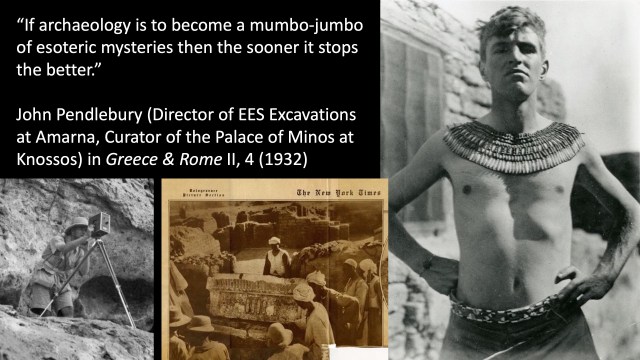

“If archaeology is to become a mumbo-jumbo of esoteric mysteries then the sooner it stops the better.” (John Pendlebury).6

Pendlebury’s point was that archaeology was pointless unless it reached beyond its practitioners to a wider audience. I have always strongly believed that it is incumbent on Egyptologists to make communicating with public audiences a part of their work. I’m not suggesting every last Egyptologist should do this but enough of us need to, and everyone should recognise how important it is. We need to be a part of the discussion – on TV, online, podcasts, social media etc. We need to make sure the voices that are heard are those with expertise – knowledge of the evidence and published literature, how to find it, how to use it etc. And these days I believe we need not to be shy in sharing our credentials. I’ve written in the past about how important it is to that the public can rely on Egyptologist to provide accurate information and interpretations and that means us making clear what our credentials are. So when I get a moment I will definitely be posting a CV to this website!

Thanks for reading! As always do let me know what you think in the comments.

NOTES:

1. I’m thinking here of a column that appeared regularly in The Guardian a few years ago called ‘Bad Science’ which was written by a medical doctor, Ben Goldacre. Each piece took some recently publicised scientific research and exposed the holes either in the research itself or that way it was reported or even manipulated.

2. Hadjimatheou, C, ‘The real Salt Path: how a blockbuster book and film were spun from lies, deceit and desperation’ The Observer, 5 July, 2025.

3. Malik, N, ‘With ‘AI slop’ distorting our reality, the world is sleepwalking into disaster’ The Guardian, 21 April, 2025

4. ‘AI is killing the web. Can anything save it?’ The Economist, 14 July, 2025

5. Portes, R, ‘Who needs experts?’ London Business School. https://www.london.edu/think/who-needs-experts. Accessed 21 September 2025.

6. John Pendlebury (Director of EES Excavations at Amarna, Curator of the Palace of Minos at Knossos) in Greece & Rome II, 4 (1932)

Calling monuments like this one in the Central Mastaba field ‘tombs’ attracted some frustrating comments at the time! The series of photos I posted starts

Calling monuments like this one in the Central Mastaba field ‘tombs’ attracted some frustrating comments at the time! The series of photos I posted starts

Slide from my talk showing one of the titles held by the official Qar and containing the name of the Great Pyramid, the ‘Horizon of Khufu’ which is written with a pyramid determinative sign.

Slide from my talk showing one of the titles held by the official Qar and containing the name of the Great Pyramid, the ‘Horizon of Khufu’ which is written with a pyramid determinative sign. Scene from the tomb of Djehutyhotep at el-Bersha showing a colossal statue being hauled into position. Via

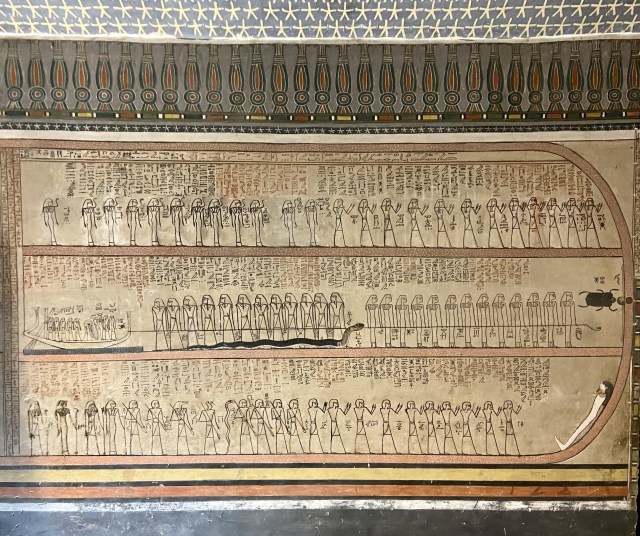

Scene from the tomb of Djehutyhotep at el-Bersha showing a colossal statue being hauled into position. Via  Scene from the tomb of Ameneminet (TT 277, Luxor) showing two deceased individuals in upright coffins, attended by mourners, in front of the tomb entrance which is surmounted by a pyramid.

Scene from the tomb of Ameneminet (TT 277, Luxor) showing two deceased individuals in upright coffins, attended by mourners, in front of the tomb entrance which is surmounted by a pyramid. Central Mastaba Field, Giza with the top of the pyramid of Khafra in the background.

Central Mastaba Field, Giza with the top of the pyramid of Khafra in the background.