Thanks to everyone who has watched my talk on ‘Pyramid Mythbusting: ancient Egypt, not ancient aliens…’. The talk was broadcast live via YouTube on 7 August 2024 and the recording has been freely available on the channel since, see here or below:

No subject in Egyptology attracts more theories than the pyramids, especially those of Giza. How they were built, who by, when and what for? For many, Egyptology’s answers to these questions aren’t good enough. The recent TV series, Mysteries of the Pyramids with Dara O’Briain in which I was one of the experts, addressed this phenomenon. The aim of this lecture is to show that, contrary to popular belief, the conventional view that the Giza Pyramids were built during the Fourth Dynasty by the ancient Egyptians, as tombs for their kings, remains the best interpretation of the available evidence, and will emphasise what that evidence is. There is no conspiracy, Egyptologists have nothing to hide, and do not stand to lose anything if new evidence emerges to cause them to alter their conclusions!

This talk is freely available to all but giving lectures like this is a part of how I earn a living so if you ‘d like to send a contribution to support my work please consider doing so via PayPal, the ‘Thanks’ button next to the recording on YouTube, or by joining the channel as a member. For more information about this please see here.

*****

First of all, my slides are here. All images in the presentation are my own unless otherwise stated.

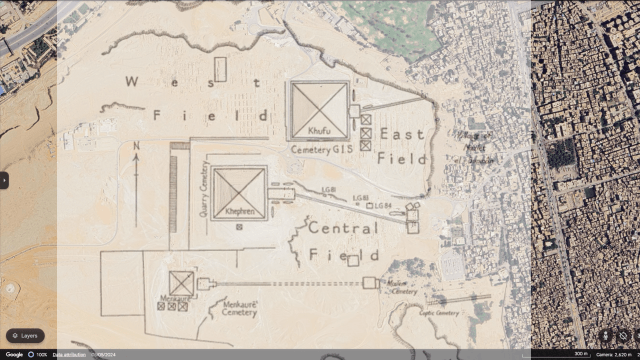

The satellite images at the start of the talk are from Google Earth which is, of course, freely accessible and great fun to play around in. For a bird’s eye view of the Giza plateau start here.

The maps I overlaid onto the satellite images are taken from the most comprehensive guide to Egyptian sites and monuments and relevant literature available, which Egyptologists commonly refer to as ‘Porter and Moss’ after the first editors, or, less frequently, the ‘Top Bib’, short for Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts Reliefs and Paintings. The first seven volumes deal with archaeological sites and inscribed objects recovered from them; the eighth deals with ‘objects of provenance not known’ i.e. objects in museums etc whose origin is unknown usually because they were sold on the antiquities market without any record of where they were found. The volume for the Giza plateau is Volume III, Part 1 which you will see abbreviated to PM III.1 or III/1. The volumes were originally prepared for printing of course but are all now freely available for download from the Griffith Institute here. They are out-of-date in some respects now, but only in the details, and as nothing has ever come close to superseding Porter and Moss, it’s still an excellent starting point for research into the plateau (and, indeed, more or less all archaeological sites in Egypt).

To search for more recent literature, in particular anything relating to fieldwork conducted at the site since Porter and Moss was published, I would recommend the Online Egyptological Bibliography. This requires a subscription fee to support the mammoth task of recording every book and article that appears in Egyptology but if you’re serious about research into Giza and its monuments – or any other subject in the field – it’s indispensable.

We are fortunate that a comprehensive overview of the site, its history and archaeology, was published only a few years ago by the two archaeologists with the most experience of working there: Drs Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass, both of whom have spent an entire research career working all over the site. Both are responsible for major new discoveries at the site, most importantly at the workmen’s settlement at Heit el-Ghurab, and for adding masses of new material and information. Their book is Giza and The Pyramids (2017) and I cannot recommend it highly enough.

I also drew heavily on three other books in the preparation of this presentation, as follows:

Lehner, M, The Complete Pyramids (1997)

Lightbody, D and Monnier, F, The Great Pyramid 2590 BC onwards. Operations Manual (2019)

Tallet, P and Lehner, M, The Red Sea Scrolls: How Ancient Papyri Reveal the Secrets of the Pyramids (2022)

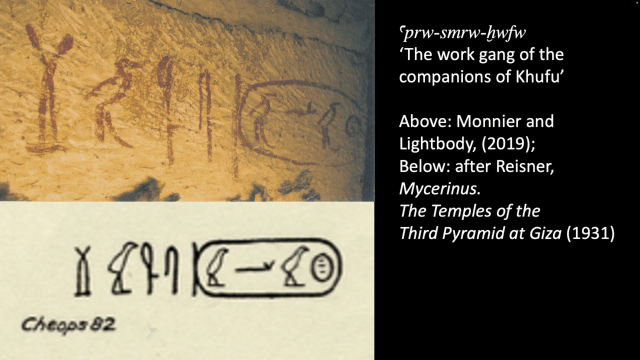

Lightbody and Monnier are specialists in ancient architecture and engineering and their book contains a wealth of interesting images and diagrams of the monuments at Giza but also elsewhere to illustrate how the Egyptians achieved these great feats of construction. Pierre Tallet is the discoverer of the ‘Red Sea Scrolls’ and the book is a brilliant and accessible account of the sensational discovery of the papyri, including the ‘Journal of Merer’ which has shed so much new light on the construction of the pyramid of Khufu, in 2013 at Wadi el-Jarf on the Red Sea.

Dating the Pyramids

Alan Rowe’s analysis of the informal inscription naming the ‘work gang of the companions of Khufu’ and others like it was published in Reisner, G A, Mycerinus. The Temples of the Third Pyramid at Giza (1931), which is freely available online via the MFA Boston’s Giza Archives website, here. Appendix E is the section in question, see here.

As I mentioned towards the end of my talk, the MFA Boston’s Giza Archives and Porter and Moss (see above), are perhaps the two richest single resources of information on Giza and its archaeology. I should also have mentioned Digital Giza / The Giza Project at Harvard University which offers yet more. Crucially, all these sources present the primary material i.e. the archaeological evidence – everything from potsherds, to statuary, to the buildings themselves, the pyramids, Sphinx and thousands of mastaba tombs – stripped, as far as possible, of any subjective interpretation. The consensus view on the when, how and what of the Giza monuments is built on this evidence, and any alternative interpretations must show how this evidence can be interpreted differently, and cannot disregard it.

We are immensely fortunate that in the case of Giza, which attracts so many alternative ideas, so much of the relevant literature is freely available online thanks to Porter & Moss, the MFA Giza Archives and Digital Giza. This is not the case for any other major archaeological site in Egypt for which far less can be done without a visit to a specialist library.

For anyone in any doubt about how much evidence there is I would urge you to take a look at the record for just one of the thousands of mastaba tombs – take for example the mastaba of Qar (G7101) which I referred to as the owner was ‘Overseer of the town of the pyramid ‘Horizon of Khufu’’. This will give you a sense of just how much material there is, and how many millions of expert-hours have been poured into building up the totality of evidence and understanding of the Giza monuments.

The standard edition (translation and commentary) of Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, the history of Egypt from which we get our idea of ‘dynasties’, is also freely available online, thanks to the immensely useful Lacus Curtius site, here. I’m currently writing a book on this sort of thing so expect to hear a lot more about Manetho in the coming months! The graphic of the Abydos kinglist is taken from pharaoh.se which is a brilliant online resource for the names of Egyptian pharaohs and related subjects such as kinglists. The Abydos list is dealt with here.

The 4th Dynasty section of the kinglist in the temple of Sety I at Abydos (photo my own).

For the pottery and the rest of the “abundant material evidence of the real ancient Egyptians and their society that built the pyramids” (quote from Lehner and Hawass, Giza and The Pyramids, 26), I would strongly recommend a visit to the website of the Ancient Egypt Research Associates, the organisation established by Dr Lehner for his research at Giza. The results of their excavations at Heit el-Ghurab and elsewhere have been published in a series of reports which are freely available for download, here. For a very detailed overview of the development of Egyptian pottery over time and how this helps archaeologists to date and interpret sites like Giza, one of the team’s expert ceramicists has published a four-volume Manual of Egyptian Pottery which is also freely available for download, here.

On the ‘Orion Correlation Theory’ which attracted so much attention in the 1990s, a handy and recent summary of the arguments and counter-arguments is Willem van Haarlem’s article ‘The Orion Correlation Theory: Past, Present, and Future?’ in van den Bercken, B J L (Ed.), ALTERNATIVE EGYPTOLOGY. Critical essays on the relation between academic and alternative interpretations of ancient Egypt which can be read online for free, here. Van Haarlem’s article also includes brief mention of the ‘Sphinx weathering‘ hypothesis. The geologist and Egyptologist, Colin Reader, is one of the main advocates for run-off rather than rainfall having caused the weathering visible on the sphinx and his article ‘A Geomorphological Study of the Giza Necropolis with Implications for the Development of the Site‘ is packed with interesting information and illustrations about the geology of the site (although, contra Lehner and Hawass, Reader believes the sphinx pre-dates the reign of Khufu, albeit not by thousands of years).

Were the Pyramid Really Tombs? (Yes they were!)

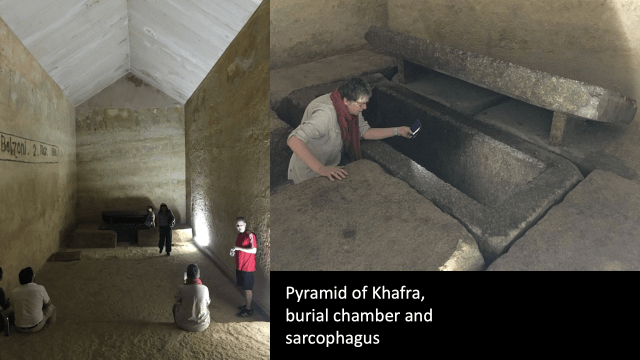

Much of my information on the human remains and funerary equipment – coffins, canopic chests etc – that have been found inside pyramids – despite the common misconception that nothing like that has come to light – comes from Lehner’s Complete Pyramids.

For more on the coffin fragments found in the pyramid of Meidum and now in the Petrie Museum please see the museum’s online catalogue here. For the fragments found in the pyramid of Menkaura and now in the BM see the online catalogue entry here. For the pyramid of Senusret II at Lahun, Petrie’s original excavation reports are available via archive.org: Illahun, Kahun and Gurob, 1889-1890 (1891) and Lahun II (1923). And his report on the pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara Kahun, Gurob, and Hawara (1890) is also freely accessible via archive.org.

The contents of the burial chamber of the pyramid of a daughter of pharaoh Ameny Qemau are described in the ministry of Antiquities Newsletter for May 2017 which is here. I was lucky enough to be present at the opening of the burial chamber and I discuss the discovery at length in my talk on ‘Egypt’s Lost Pyramid’, here and below.

For the Pyramid Texts of the Pyramid of Unas (and generally) I strongly recommend the Pyramid Texts Online.

The burial chamber in the pyramid of Unas, the first to be decorated with the Pyramid Texts

The Burton photographs from the tomb of Tutankhamun that I used to illustrate the phenomenon of tomb robbery are all available online via the Griffith Institute’s Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation, here.

My presentation included scenes e.g. of mourning, the funerary procession etc. from various tombs. In most cases I used my own images but for more information on these tombs featured (in addition to any mentioned elsewhere on this page) please follow these links:

Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, Saqqara (5th Dynasty): Osirisnet

Rekhmira, TT 100, Luxor (18th Dynasty): Davies, N de Garis, The tomb of Rekh-mi-Rē at Thebes: Volume I and Volume II (1943)

Meryneith, Saqqara, (18th Dynasty): Raven, M J et al, The Tomb of Meryneith at Saqqara (2014)

Ankhmahor, Saqqara (6th Dynasty): Egyptian Monuments

Ramose, TT 55, Luxor (18th Dynasty): archive.org

Ameneminet, TT 277, Luxor: Osirisnet

Scene of mourning, tomb of Ankhmahor, Saqqara (6th Dynasty)

I think that’s everything but if there’s anything I’ve forgotten or should add please let me know!

*****

Please note: the links to Amazon on this page are ‘associate links’. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.