Professor Kenneth Kitchen, the great scholar of ancient Egypt and the Near East passed away recently.

Me and Ken in his back garden in Woolton, Liverpool in November 2008.

I’ve been fortunate enough to get to know, to some extent, most professional Egyptologists in the UK in the last 25 years or so. Sadly we have lost some very highly regarded members of the community in the last year or two including Professors Barry Kemp, Geoffrey Martin and Harry Smith. I knew them all personally. Others have written eloquently about their lives and achievements and doubtless much will be written about Kenneth Kitchen (see e.g. here). In his case I wanted to add a personal appreciation to let the world know that I will be forever grateful to him for the support he gave me at a very difficult moment, without which I’m not sure I’d still be doing Egyptology.

Ken was a giant of the field. He was the author of numerous books, articles and reviews, and must have taught thousands of students at the University of Liverpool where he spent his entire career from the day he started his studies as an undergraduate. Two of his publications have become indispensable research tools, known universally to specialists by their abbreviations: KRI for Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions, his comprehensive, hand-drawn anthology of hieroglyphic texts of the 19th and 20th Dynasties; and TIP (although Ken himself referred to it as ‘Thip’) for The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt which gathers and organises a vast amount of information on the 21st to 25th Dynasties which, although his interpretations have now been challenged, has advanced our knowledge of the period enormously by giving a coherence to the evidence that it never had before.

Front cover of Prof Kitchen’s ‘Thip’.

The story of my friendship (I think I can say that?) with Ken is one of having my perceptions drastically altered. I first came across him as a contributor to the Channel 4 television series ‘A Test of Time’ in which he was cast as the antagonist, opponent of the revisionist chronology of the series’ presenter, David Rohl. Watching the show at face value it was hard not to be taken with Rohl’s exciting new ideas, and persuaded by his argument that the establishment – represented by various scholars including an unimpressed Jean Yoyotte, but mainly by Ken – was simply uninterested in listening to any new ideas. I was a very keen undergraduate at the time the show was broadcast, and loved every episode. In my memory of it Kitchen came across as a sour old man, with wild, white hair and eyes half closed, every bit the bad guy to David Rohl’s younger, more charismatic outsider. At the heart of Rohl’s new chronology was the radical idea that the 21st and 22nd Dynasties had largely overlapped, lowering that dates at which everything before that time happened, with dramatic implications for the way we look at archaeological levels at sites around the ancient world. As the author of The Third Intermediate Period it was inevitable that Ken would embody the establishment theory that Rohl was trying to knock down.

By chance I had chosen to study at the University of Birmingham where the leading Egyptologist, Dr Anthony Leahy, was himself a specialist in the same period. I soon learned that David Rohl’s ideas were not taken any more seriously by Dr Leahy than by Prof Kitchen, and indeed most of the ‘pillars’ of the new chronology were ably dismissed in print by scholars such as Aidan Dodson soon after the TV series was shown. Kitchen’s book was indispensable for the study of the TIP and I had borrowed it from the university library on short loan so many times that when I was given a voucher for some new online bookshop called ‘Amazon’ I used it to buy my own copy. Leahy and Kitchen were by no means aligned however: Dr Leahy had offered his own radical revision of Kitchen’s chronology a few years beforehand. However, unlike David Rohl’s new ideas which had got a lot of publicity but little or no acceptance among scholars, Leahy’s revisions passed almost everyone bar a tiny number of specialists in the period by, but had not been rejected, and indeed his reconstruction is now accepted by Egyptologists as the best way of interpreting the evidence.

For more on the substance of the debate see my talk, ‘Egyptians, Libyans and Kushites: The Third Intermediate Period UNTANGLED!‘ and the notes here.

Ken had rejected Leahy’s revised chronology in the preface to the third edition of TIP in 1995 in typically robust style, describing various aspects of it as “entirely unjustified”, “wildly improbable”, “no factual basis”, “clear failure”, “All this is clutching at straws” …and so on. This was characteristic of Ken’s style in print: he could be a little dogmatic in hanging onto his preferred way of looking at things and was not afraid to treat alternative ideas with disdain. It always made for entertaining reading but perhaps didn’t endear him to those on the receiving end of all his scorn. I was told while still a student in Birmingham that Professor Kitchen could never be an external examiner for our students as he would simply put a line through the students’ submissions and write ‘WRONG!’ I have no idea if this was true or not but at the time it chimed with what I knew of him from ‘A Test of Time’.

I went on to do a master’s degree with Tony Leahy in Birmingham straight after my BA. My dissertation focussed on Twenty-fifth Dynasty officials in Thebes and the difference between Kitchen and Leahy’s respective reconstructions of the preceding TIP had a significant bearing on the way I looked at things. According to Ken Kitchen’s view, Thebes had been under the control of a line of kings based in the Delta for most of the period leading up to the 25th Dynasty. According to Leahy, Thebes had been independent. Naturally I chose to base my interpretations on Leahy’s reconstruction. After my master’s had finished, with aspirations to make a living in the field, I submitted an abstract based on my dissertation to the second Current Research in Egyptology (CRE) conference which would be held in January 2001, in Liverpool – home of Prof Kitchen. I was a young scholar of the ‘Birmingham School’ going into the lion’s den. At first I thought there would be no way Ken Kitchen would attend a student conference – he was too important and probably didn’t like young people (or anything very much at all, I thought). And then I discovered that he would be giving one of the keynote lectures, on the first day. Oh no, I thought, he will be there… But then he probably wouldn’t stay to listen to the students give their papers, would he..?

Anyway, when it came to Ken’s turn to give his talk, a few hours before mine, he was nothing like what I’d been expecting. Tall, full of energy, and loads of jokes! Wow, I thought, he’s funny, and not at all like the nasty little man I’d come to expect. Still, I knew from his writing that he did not like anyone disagreeing with his ideas so of course I was still very much hoping that he wouldn’t be there for my talk. When my turn came I looked round the room and couldn’t see him so I relaxed and got on with reading my paper, safe in the knowledge that no-one would know what I was talking about…

At the coffee break afterwards, feeling relieved that it was all over, I was having a nice chat with someone when suddenly from behind me there was a sort of minor explosion, a ‘HELLO!’, and a hand thrust itself forward for me to shake. It was Prof Kitchen, full of enthusiasm and encouraging comments. He told me he had really enjoyed my paper and asked if I could give him the reference to an article on a scrap of evidence that had recently revealed the existence of a previously unknown Fourth Priest of Amun. I couldn’t believe it… Everything I had been led to believe in Brum was wrong, Prof Kitchen turned out to be a lovely, kind and supportive man.

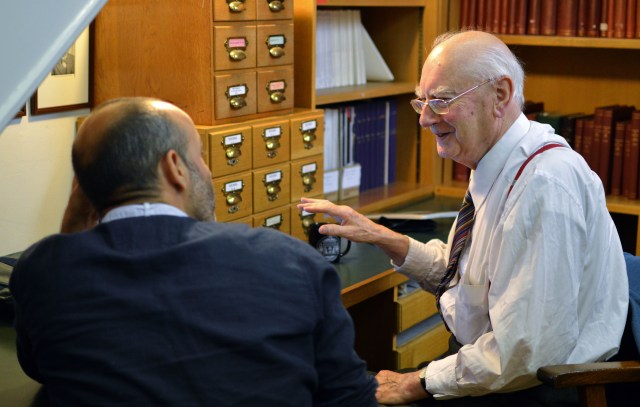

Going through old photos with John Johnston in between interviews for the EES’ Oral History Project.

I had already started working for the EES by the time of the conference and saw him semi-regularly on the scene after that. I got to know him much better a few years later in 2008 when he became the first interviewee for an ‘Oral History of Egyptology‘ project which we had recently started at the Society. John Johnston, a former student of Ken’s in Liverpool and an EES Trustee by this point, suggested Ken would be the perfect candidate and so, armed with newly purchased recording equipment, we travelled up to Ken’s home where we stayed for the weekend to record the conversations, John asking the questions, me manning the equipment.

Prof Kitchen talks about the beginnings of his Ramesside Inscriptions for the EES’ Oral History Project.

Ken was a very gracious host, providing comfy (if VERY dusty!) bedrooms and cooking our meals. This despite almost every spare inch of his house being given over to his work, mostly to his enormous collection of books, which were everywhere. He talked and talked, about everything from his childhood and how badly affected he was by the Second World War, how he set his heart on Egyptology and his entire family moved to Liverpool – to the house in Woolton where John and I stayed – to support him. He talked about this career of course, and his current daily routine. He had probably been retired for around twenty years by this point and yet he was still dedicating almost all his waking hours to a series of publications projects, mostly philological, involving texts and languages from around the ancient Mediterranean world, not only Egypt. He had a staggering capacity to read ancient languages, and to assimilate knowledge of an incredibly broad range of cultures. How any one person could become so expert in so many peoples and places is a marvel and very humbling. He was frustrated however that didn’t have as much energy as he used to, and couldn’t get through as much. Still he did eventually find time to re-tell some of the stories he told us during the interviews in an autobiography, In Sunshine and Shadow (2016).

Ken with the painting by Amelia Edwards which he generously donated to the EES (see here).

He was a generous supporter of the EES and donated a painting made by Amelia Edwards to the Society for its collection in 2009. If I remember rightly it had been given to him by Rosalind Moss of the legendary ‘Porter and Moss’. He came to London on several other occasions during my time at the Society to give lectures and seminars and, on one very memorable occasion, travelled down to meet a group of our ‘scholars’ from Egypt. They were quite bowled over to meet the great man. A creature of habit, he always stayed at the PEN Club near Russell Square, and I remember from a few occasions in restaurants that he ate very quickly, his knife and fork rushing busily around the plate, and always asked for apple juice.

Prof Kitchen and I with four of the six EES scholars in 2015, L-R: Yasser Abdelrazek, Ahmed Neqshara, Mohamed Abuelyazid, me, Ken, Hesham Hussein.

Anyway, to the main reason why I wanted to write about Prof Kitchen.

I went through a pretty tough time around 2009-2011. I’d had a bad experience doing my PhD: politics at the EES had meant that I’d had to go somewhere other than Birmingham for my doctorate; my new university had changed my supervisor several times, and none of those I’d been given had provided the support I was hoping for (or any at all really). Although I’d finally submitted my thesis in summer 2009, a few months later I’d had a bad viva and was asked to go away and do some more work on it (‘major corrections’). A few days before the exam my mum had, out of the blue, been diagnosed with a very serious form of leukaemia and I was really looking forward to passing my PhD, getting it out of the way and giving the family some good news. I didn’t have the emotional bandwidth to deal with not passing, and having to go back and do more work on it. Mum was in hospital for the next ten months and eventually died in September 2010. I felt so let down by the university, my supervisors and by the examiners (well, the internal examiner) that I was very tempted not to re-submit. My great fear was that I would fail at the second attempt (you only get two gos) and I didn’t think I could take the humiliation and sense of having failed at my chosen subject.

I don’t remember talking to him about this but Ken must have known I was thinking of giving up. In summer 2011 I was finally working on my thesis again. Ken called the office to talk to me about something but was told that I was taking some time away to get the writing finished. He wrote me a letter. A perfect letter.

A part of Ken’s letter (now in a frame): “My view of things like PhDs is that they are simply a piece of additional “armour-plating” in a snobbishly uncomprehending world; to be “Dr.” Chris Naunton in some ways may prove a practical help in some quarters. But you are you (with all your already inbuilt abilities and excellencies!!!), whether you have this doctoral tag or not; do your best, but don’t let it distort your life…”

It strikes me that rarely in any circumstances has anyone ever shown so clearly that they know exactly what I’m feeling, and said exactly the right thing to make me feel better. As a giant of our field, what he said about me and my work carried a lot of weight. I was already very fond of him but I’m still awed, even now, by the perceptiveness of his understanding of what I was going through, and ability to say just the right thing. I got nothing like this from my university supervisors. It’s a rare gift to have that understanding, and a rare soul who takes the trouble to help another person like that, and I will be forever grateful that I was the beneficiary of it.

Ken’s great legacy will be his enormous contribution to scholarship in so many fields. He really was a giant and he will rightly be remembered for that. For me he started out – before I met him – as a nasty little man, but became a twinkle-eyed, charming, effusive, warm and funny friend – as soon as I came across him in person. I’m sure I won’t be the only person with stories like this but I wanted to share this one because to me, more than anything else, he was just a wonderful person.

“Do the best as you can for yourself and help the other.” Thanks to Hesham Hussein (seen here at Doughty Mews with Ken) for the reminder of this phrase of Prof Kitchen’s.

Thank you Ken.