Well, this is exciting…

In a press release posted by the Luxor Times to social media on Tuesday earlier this week, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA) has announced the discovery of the tomb of pharaoh Thutmose II, by an Egyptian-British mission led by Dr Piers Litherland.

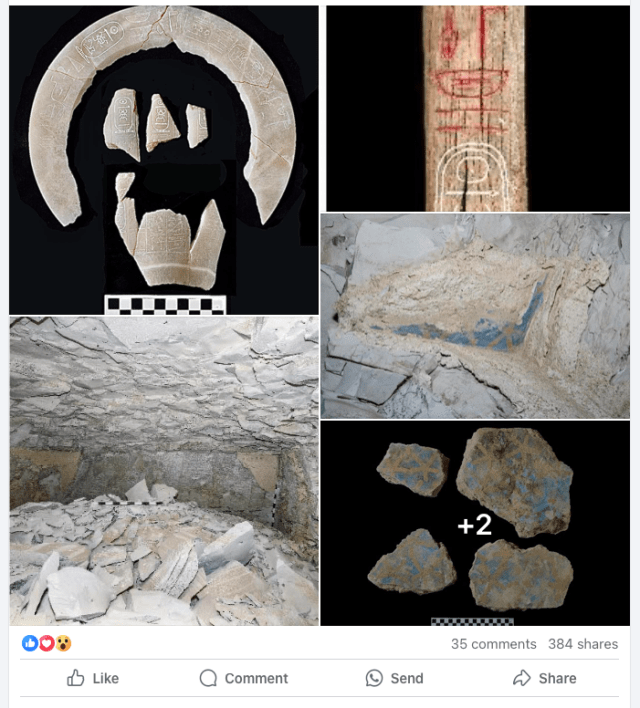

Screenshots from the Luxor Times post on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/luxortimesmagazine

When things like this get announced I’m often asked for comment by the media. The discovery of new material – which is happening all the time, incidentally – there are dozens, maybe hundreds, of projects working the field in Egypt every year and they’re not all finding nothing! – is always interesting, but if I’m really honest I’m often not that excited and sometimes don’t have much to say. Press releases are often full of hyperbole but light on really good information; what can one say about the latest discovery of a cache of brightly coloured coffins without knowing much more about the circumstances of the find, the details of the material? ‘They are very pretty, yes…’

This week’s announcement is a bit different. The tomb of a king does not come up very often (although more on this below), and having written a book about the Lost Tombs… of various pharaohs it’s of particular interest to me. And as I’ve been asked to give several interviews about it this week I thought it was about time I got my thoughts together. Here goes…

What do we know?*

Most of the information that follows here comes from Litherland, P, ‘Has the Tomb of Thutmose Il been found?’ in Egyptian Archaeology 63 (2023), 28-31 – note the publication date – more on this below!

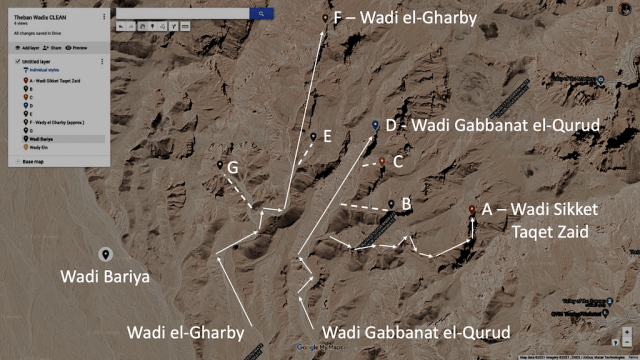

The Western Wadis. The map is taken from my talk on the subject and the possibility that Herihor might have been buried in the area, which is online here.

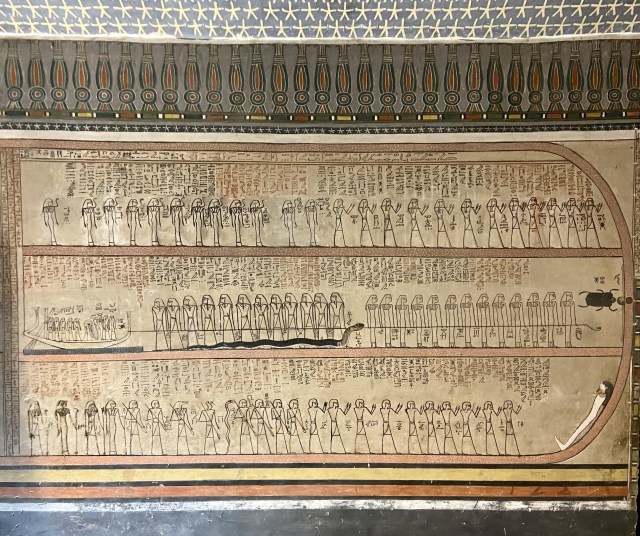

The tomb has been designated C4 by the discoverers, and is located in a wadi, long known as ‘C’ which is part of the remote ‘Western Wadis’ region, approximately 2.45 km from the Valley of Kings (my Google map showing the area is here). The tomb is rock-cut, and comprises two corridors and four roughly rectangular chambers of varying sizes. It has suffered badly from repeated flooding and is now in a very poor state of preservation. The floor of the corridor was coated in white plaster, and although little decoration survives, a small section of a starry ceiling – a distinctive feature of pharaonic tombs – has survived, along with traces of a khekher frieze. Fragments of the Amduat (‘what is in the netherworld’) – the main feature of the decoration of kings’ tombs at this time – have also been found.

KV 35, tomb of Amenhotep II. The twelfth hour of the Amduat with a khekher frieze and the very edge of a starry ceiling visible above.

Of the burial equipment, fragments of alabaster vessels belonging to Thutmose (deceased) and mentioning his Great Royal Wife (and half sister), Hatshepsut have been recovered, but little else: no sarcophagus, canopic equipment or shabtis. It seems the the king’s body was interred here as the presence of “large quantities of typically early 18th Dynasty ceramic plates, bowls, lids, amphorae and white-washed storage jars” (Litherland (2023), 31) would suggest, but also that the tomb was badly damaged by flooding only a few years after the king’s death and that his burial was therefore moved, leading to the suggestion that there may be another, as-yet undiscovered tomb nearby.

One of the team’s archaeologists, the very experienced Mohsen Kamel, was quoted in The Guardian (‘Archaeologists discover first pharaoh’s tomb in Egypt in more than a century’) as saying: “The possible existence of a second, and most likely intact, tomb of Thutmose II is an astonishing possibility.”

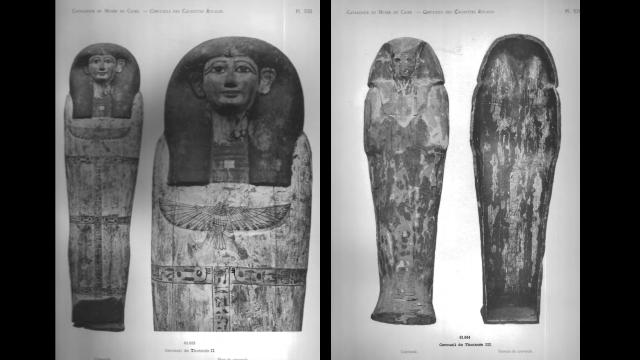

It seems very unlikely that any second tomb would be found intact however, as we know that the mummy of Thutmose II was removed from wherever it had been laid to rest when, towards the end of the New Kingdom, the mummies of almost all pharaohs of the period were removed from their tombs and re-buried in two secret caches. Thutmose’s mummy was found in tomb TT 320 (‘The Royal Cache’) in the late 19th century and is now on display in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation in Cairo. As part of the caching process the burial equipment of the kings was stripped of any precious materials, probably as Egypt’s rulers needed to reclaim the wealth that was tied up in the precious metals and inlays of the coffins, jewellery and other items the kings were buried with. (More on this in my talk here).

L: the coffin of Thutmose II discovered in the ‘Royal Cache’ tomb TT 320. R: the coffin of Thutmose III showing clear signs of an adze having been used to scrape off any gilding and with inlaid eyes removed. Both images from Daressy, G, Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire N° 61001-61044. Cercueils des cachettes royales (1909) which is freely accessible online via archive.org

So, even if there another tomb of Thutmose II to be found somewhere, it’s very unlikely that it will be any more intact than any of the other royal tombs found in the Valley of Kings and elsewhere. Nonetheless, it could yet yield some very exciting stuff including the sarcophagus, canopic equipment and shabtis mentioned above.

UPDATE (22 Feb 2025): an article headed ‘‘You dream about such things’: Brit who discovered missing pharaoh’s tomb may have unearthed another’ has been published in The Observer online today (here) in which Dr Litherland claims that the mummy thought up to now to be that of Thutmose II cannot in fact be his as it’s the body of a man of around 30 years old which is too old for Thutmose II. This is the basis for the argument that a second, intact, tomb of Thutmose II may yet be found. There is a certain amount of evidence that suggests that Thutmose II may not have reached the age of 30 but it’s not entirely conclusive. It’s also true that there was some mixing of the material found in the Royal Cache; but the coffin certainly bears Thutmose II’s name, as did the mummy itself which was labelled with identifying ‘dockets’. Perhaps those responsible for the caching got completely the wrong body… It still seems unlikely to me but if an intact tomb with Thutmose II’s mummy does turn up in the Western Wadis then I’ll be proven wrong!

The mummy identified as being that of Thutmose II – image from Smith, The Royal Mummies (available online here).

Significance?

Well, the discovery of the tomb of a pharaoh is exciting, full-stop. In this case, it’s the tomb of a king who lived and reigned during a celebrated period in Egypt’s history, the Eighteenth Dynasty, which, along with the 19th and 20th constitutes the New Kingdom. Egypt was the great power in the region at this time, its kings conquering other people and places all around through military force, bringing in great wealth in the form of annual ‘tribute’ (we’re in charge now so give us all your stuff). It was a time of great building, and famous pharaohs including several by the name of Thutmose, several Amenhoteps, Akhenaten, Tutankhamun and Ramesses the Great. It was also the time of the Valley of Kings, and most of the tombs of pharaohs of this period of five centuries or so are well known. Thutmose II’s was conspicuously missing, one of the great ‘Lost Tombs’ – until now.

The king himself remains fairly obscure however: we know of few monuments constructed in his name, and few inscriptions, and it seems likely that he reigned only for a very short time, perhaps as few as three or four years. He is, however, an important part of a very interesting period in Egypt’s history.

First, he was son of Thutmose I who is much better-known and one of the pharaohs who helped establish Egypt’s dominance in the early New Kingdom. His son and successor, Thutmose (III), would rule for 54 years and became perhaps the greatest warrior pharaoh of them all. In between the great campaigns of Thutmose I and Thutmose III we get one of the most fascinating stories in Egyptian history: that of Thutmose II’s half sister, Hatshepsut, who he took as his Great Royal Wife. Thutmose III succeeded his father when he was very young leaving Hatshepsut in charge of the country initially as regent, but at some point during the early years of Thutmose III’s reign she assumed the role of pharaoh.

Hatshepsut, her skin of the red colour usually used to depict men and wearing a divine beard. From her temple at Deir el-Bahri and now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Evidence from early on during this time shows Hatshepsut adopting more and more of the trappings of kingship but only gradually, as if easing herself into the role while navigating the challenges of doing so as a woman in what, by convention, was a role played by a man. Initially she was shown as a woman but with the full titulary of pharaoh, but eventually she would even adopt male features such as the divine beard. After her death her image and names were deliberately erased, and she was omitted from later king lists, her reign deliberately forgotten.

Hatshepsut being purified by Horus and Thoth, her image and names erased so carefully that the hieroglyphs can still be read(!). Room XII close to the granite sanctuary of Philip Arrhidaeus at Karnak.

As scholars began to piece the story back together in modern times they originally concluded that she was a megalomaniac who seized the opportunity to take the throne while her step-son was too young to stop her, but this has now been challenged. The erasure of her memory seems not to have started until some twenty years after her death, and was perhaps related to a struggle to decide who would succeed Thutmose III as he grew old. He was eventually succeeded by Amenhotep (II) who was not directly related to Hatshepsut – was there a rival from her side of the family whose claim would be weakened by the removal of any trace of her reign? In any case, Hatshepsut’s elevation to pharaoh may simply have made most sense as she was ruling the country anyway while her step-son was incapable. Peter Dorman’s article ‘Hatshepsut: Wicked Stepmother or Joan of Arc?’ (here) explains all this in more detail and more eloquently. He concludes that “Both Ineni’s biography and Senenmut’s graffito indicate that Hatshepsut was the effective ruler of Egypt from the death of her husband. The question was not the wielding of power but how to represent it in a public context.”

The northern obelisk of Hatshepsut at Karnak, the largest ever erected in its day, still standing more than 3,000 years later.

Hatshepsut’s reign was a great success, notably in her building achievements – the largest obelisks ever erected in Egypt up to her time, an exquisite bark shrine at the centre of the Egyptians’ most important temple at Karnak, and her mortuary temple which architecturally is perhaps the finest Egypt ever produced, a superbly harmonious marriage of man-made design and the natural landscape.

Hatshepsut’s spectacular mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri.

In seeking a narrative that would legitimise her she emphasised her connection to her father Thutmose I in the temple decoration, but also created the story of her mother’s union with the god Amun-Ra, the divine conception and birth of pharaoh which would become one of the enduring myths of Egyptian kingship.

Hatshepsut was a great pharaoh and her husband Thutmose II’s main claim to fame is probably that he was married to her!

Development of the royal tomb in the early New Kingdom

For me, the most interesting aspect of the new discovery is that it adds to what we know about the development of the royal tomb in the early New Kingdom. This was a time of transition. The Valley of Kings is one of the defining features of the New Kingdom, it was the burial place of almost all the pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty, and all those of the Nineteenth and Twentieth with the exception of that of Ramesses VIII whose tomb hasn’t yet been identified, and Ramesses XI for whom a tomb was cut in the Valley but which was never used as the king had decisively lost control of Thebes to the Chief Priest of Amun by the end of his reign, which itself marks the end of the New Kingdom. The Valley didn’t come into use until a few reigns into the Eighteenth Dynasty however. During the preceding Seventeenth Dynasty, the kings were buried somewhere in the Theban foothills in the area we now call Dra Abu el-Naga. Their tombs were excavated in the mid-19th century and several coffins and other equipment removed, but the precise location of the tombs themselves has subsequently been lost – as they were undecorated and are now stripped of any identifying material – thanks to the archaeologists – we’d have no way of knowing, even if they did turn up (perhaps they already have). The location of the tombs of the first two kings of the period, Ahmose I and Amenhotep I, remains unknown (on the latter see my Lost Tombs book and this lecture). The first tomb to be cut in the Valley of Kings was probably the one we now refer to as KV (Kings’ Valley) 20. This appears originally to have been the tomb of the third king of the period, Thutmose I, which was subsequently also used by his daughter Hatshepsut after she became pharaoh. The burial chamber was found to contain a sarcophagus for each of them.

KV 20. Plan created by the Theban Mapping Project, via https://thebanmappingproject.com.

Searching for the perfect location for the royal tomb

This was not Hatshepsut’s first tomb. For members of the elite, construction of a tomb would be well underway during your lifetime and before she ever became pharaoh a tomb for Hatshepsut was cut in Wadi A, not far from Wadi C where the new tomb has been found. Her ‘cliff tomb’ was identified in 1916 by Howard Carter in proper Indiana Jones circumstances: Carter was dispatched by night into the desert to investigate a discovery by two rival groups of looters who were fighting over the spoils. Access required abseiling down a cliff on a rope – Carter cut the looters’ rope preventing them from escaping and then lowered himself down to see what was going on… (More on this in my talk on Herihor and the Western Wadis here).

This prompted Carter to look into the possibility that there might be other tombs in the area and this led him to the map the western wadis and thereby to lay the groundwork for future investigations although he made no further major discoveries there himself (might he have returned had he not been somewhat diverted by the discovery of the tomb of a certain Tutankhamun a few years later?). It was already known that the ‘tomb of three foreign wives of Thutmose III’ – which was found to contain a lavish haul of treasure – was in the area, and Carter found hints that Hatshepsut’s prominent daughter Neferure was also buried nearby. Many years later John Romer had proposed that the tomb of the Twenty-first Dynasty priest-king Herihor might be found in the area and testing that hypothesis appears to have been part of the original reason for the current project. They found no tomb of Herihor (and did find evidence to dismiss the idea) but they have made a string of very interesting discoveries, demonstrating that the Western Wadis were far more important as the burial place of members of the 18th Dynasty royal family than had previously been suspected.

The discovery of the tomb of Thutmose II raises the stakes even higher of course.

Filming inside KV 34, tomb of Thutmose II’ son and successor Thutmose III, in 2019. Note the Amduat, khekher frieze and starry ceiling, all present also in the newly discovered tomb C4.

So, Thutmose I was buried in the Valley of Kings. We also known that Thutmose III was buried there in KV 34. Another tomb KV 38 is very similar in design to KV 34 and appears to have been cut for Thutmose I. For many years it was believed that this was his original tomb but it is now thought that he was first buried in KV 20, and that his grandson Thutmose III subsequently cut a tomb very similar to his own and reburied his grandfather in it, perhaps to reclaim Thutmose I and separate him from Hatshepsut.

Now, with this new discovery, it seems that while Thutmose I sought to break new ground by having himself buried further away from the Nile Valley than his Seventeenth Dynasty predecessors in the high desert wadi that would become the Valley of Kings, Thutmose II decided to go elsewhere, he and his wife Hatshepsut building tombs for themselves even further away from civilisation in the Western Wadis. It’s not difficult to imagine the king’s surveyors and architects searching for the perfect place, well away from would-be robbers perhaps. As the autobiography of Thutmose I’s architect Ineni says: “I inspected the excavation of the cliff-tomb of his majesty, alone, no one seeing, no one hearing.”

The archaeologists’ discovery that tomb C4 was so badly affected by flooding perhaps suggests this taught the ancients that this wasn’t quite the right place. Perhaps this and Hatshepsut’s desire to associate herself closely with her father prompted her to move back to the Valley of Kings, a decision that was then followed by Thutmose III and almost every pharaoh for the next few centuries.

Not New

A few points of clarification… The suggestion that C4 is the tomb of Thutmose II is not new – it was published by Dr Litherland in the EES’ magazine Egyptian Archaeology in autumn 2023, and this is, as far as I know, by far and away the best source of info on the new discovery. Indeed it’s not clear to me what exactly is new since the time that article was published. The Luxor Times post says:

“…as excavations progressed this season, new archaeological evidence confirmed that the tomb belonged to King Thutmose II. Further analysis revealed that it was Queen Hatshepsut, both his wife and half-sister, who oversaw his burial.”

But the 2023 articles concludes with: “a tomb of Thutmose Il does indeed seem to have been found”.

The 2023 article contains photos and plans of the tomb, and of the main identifying features including the starry ceiling, Amduat fragments, and alabaster vessels. If you want to read more about the tomb I highly recommend getting a copy of EA 63 (via the EES, here)!

False Claims

More importantly, there are a number of claims made in the Luxor Times post which are simply not true:

The idea seems to have taken hold that this is ‘the first royal tomb to be found since the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922’ (as per the Luxor Times post), but there have been several others, most notably the royal tombs of Tanis (1939 onwards) in which the burials of several kings of the Twenty-first and Twenty-second Dynasties were found (more on this in my talk on the ‘Silver Pharaohs’ here), but also including the tomb of pharaoh Senebkay at Abydos in 2014 (see here), and the pyramid of princess Hat______ at Dahshur in 2017 (see here, and another talk, ‘Egypt’s Lost Pyramid’, here).

The tomb of pharaoh Senebkay which was discovered in 2014.

Elsewhere in the same post the Luxor Times says tomb C4 is the ‘First Royal Tomb Found in Theban Necropolis Since the Discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb in 1922’ (my emphasis). This would exclude the discoveries mentioned above, but not the family burials of two wives and a son of Amenhotep III that Dr Litherland’s team discovered in previous seasons.

It’s also claimed that C4 is ‘the last missing royal tomb of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty’. But even if one takes ‘royal tomb’ to mean the tomb of a pharaoh here and not simply that of any old member of the royal family, then what of the tombs of Ahmose I, Amenhotep I, Ankhkheperure of the late Amarna Period (whether you believe there were two pharaohs who took this name or only one there’s at least one further missing tomb) the location of all of which remains unknown? Perhaps I’m being too pedantic…

In any case, it’s great news and Dr Litherland and his team, our colleagues at the MoTA and all concerned deserve our warmest congratulations!

Further reading / watching

As per the references above I wrote about a lot of what’s discussed above in my book Searching for the Lost Tombs of Egypt.

I’ve also given talks on several of the subjects discussed: I’ve just made my lectures on Herihor (and the western wadis) and the caching of the Royal Mummies freely available to all. Talks on some of the tombs of the Eighteenth Dynasty that remain ‘missing’ are available already including Amenhotep I, and Ankhkheperure / Smenkhkare / Nefertiti / Neferneferuaten (and how to make sense of this confusing mass of evidence and names!). My most recent talk was on Hatshepsut (the day the discovery of C4 was announced!) – this one is available to channel members only but all are very welcome to join of course!

UPDATE: The above previously stated in error that Hatshepsut ‘cliff tomb’ was found in Wadi C, when in fact it lies in Wadi A. This has now been corrected. My thanks to Ted Loukes (via Facebook) and @aigineus (Instagram) for pointing this out!